Whenever they had any difficulty in unscrewing a component, they simply broke it off.[3]

It was 22 April 1918 and the six police officers had been sent to the printing works of Samuel Street – printer of the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF)’s newspaper the Tribunal – in Streatham to break up all of his machinery. Before long they had destroyed – or seized – over £500 (£25,000 in today’s money) worth and were carting off books, invoices and stationary, in addition to the broken machines.

They never produced a warrant.

‘We have done for you this time!’

That same day, police also swooped on the publishing offices of the Tribunal, at 5 York Buildings, a few minutes walk from Trafalgar Square.

After ascertaining that she was responsible for the backpage of the 11 April issue (calling on citizens to ‘throw off the bondage of conscription’ and ‘stop the war’), they demanded of the paper’s publisher, Joan Beauchamp (pronounced ‘Beecham'[4]), that she tell them the name of the editor. After warning her of the possible legal repercussions of her refusal, the officers proceeded to search the office and seized a number of books and papers.

‘We have done for you this time!’, a CID officer told Lydia Smith, the young head of the NCF’s Press Department.[5]

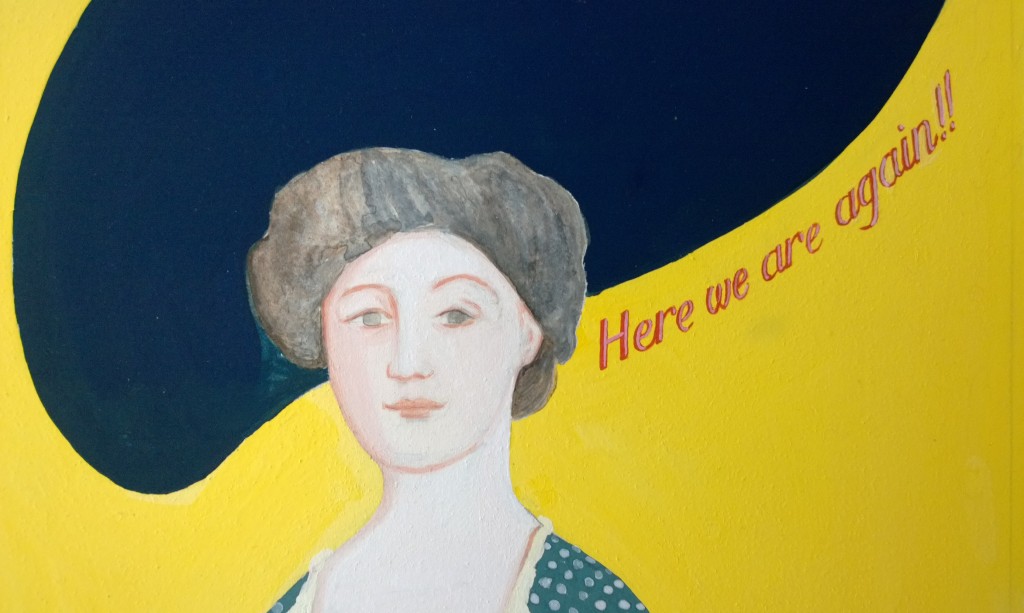

‘Here we are again!!’

The destruction of Street’s press was the culmination of many years of harrassment and repression of the Tribunal by the authorities, including legal actions against its distributors, raids on its offices, threats against its previous printers, the National Labour Press – and (ultimately) the dismantling of its machinery – and the prosecution of the Tribunal‘s publisher.

Nonetheless, three days later the Tribunal came out on schedule as a one-page leaflet, cheekily headlined ‘Here we are again!!’.

In the closing section (‘We stand for liberty’), the paper noted that:

‘The press in this country is no longer free; it is bound hand and foot, and is the servile tool of those who would fasten militarism upon us. But in spite of that we still believe that liberty of the press is as much worth struggling for, and being persecuted for, as it was in the days gone by … We have no fear of the ultimate result of the conflict between the spirit of violence and the ideal for which we stand.’

Moreover, despite their best efforts, the authorities were never able to shut down the Tribunal, which continued to be printed throughout the remainder of the war and beyond, with its final issue being published on 8 January 1920.

How did they manage it?

This remarkable achievement was possible because by 1918, with almost all of the NCF’s male leadership in jail, the administrative work of the organisation was largely being conducted by a formidable team of women, many of whom had cut their teeth in the pre-war movement for women’s suffrage. [6]

In late 1917, the group had decided that Beauchamp and Smith should share the work of editing and publishing the Tribunal, but that only Beauchamp’s name would appear in the paper as the publisher (a legal requirement). According to David Boulton, ‘The two women agreed between themselves that Joan Beauchamp should appear as publisher, and if necessary go to prison, leaving Lydia Smith free to continue the work’. [7]

‘After the enforced shutdown of the National Labour Press in February, Smith had been commissioned by the NCF national committee to buy a small handpress, type and a stock of paper. This equipment, hidden in the home of a sympathetic printer, was brought into action when Street’s press was dismantled. For almost a year this clandestine press, manned by a volunteer printer and compositor, produced the weekly edition. Since Scotland Yard was constantly on the look out for the secret press, these men were obliged to be extremely careful in their operations. On at least one occasion the press had to be moved when neighbours began to comment about odd noises.’ [8]

An impoverished-looking woman with a baby carriage who visited the office every few days, apparently looking for charity, was actually smuggling proof sheets for the paper in her carriage. [9]

Speaking decades later, in an episode of the BBC television programme Yesterday’s Witness, Smith explained that:

‘[W]hen we came out [with] “Here we are again!!” … Scotland Yard took it very badly. And for … eighteen months they tried to find out how we printed it, and where we printed it, and who was doing it … They took a room opposite us … and kept watch on us … but they never found out, partly because they were so convinced that I was sending in for a man. They couldn’t believe that – I think I looked very young in those days – and they couldn’t believe that I was the editor, they didn’t believe it for a moment.'[10]

About the women named on the poster

A key figure in the (non-militant) National Union of Women’s Suffrage Socities (NUWSS) before the war, Catherine Marshall resigned from the latter in 1915 to work first for the Women’s International League (a spin-off of the famous Women’s International Congress at the Hague – an event which she had helped to organise), and then for the NCF (of which she became the acting Honorary Secretary).[11] Described by the Labour Leader as ‘the most able woman organiser in the land’, ‘she attracted to the national office a formidable team of militant pacifist women’. [12] She once calculated that, as a result of her work for the NCF she was liable to 2,000 years imprisonment. [13]

From an army background, Violet Tillard was another former suffragist. [14] She headed the NCF’s publication department. In August 1918 she was sentenced to 61 days imprisonment for refusing to divulge the name of the printer of a privately circulated issue of NCF News. Prior to her arrest ‘she decided … to refuse to obey those prison rules which she felt to be immoral and enforced with the object of degrading prisoners’.

A suffragette and a socialist from Somerset, Joan Beauchamp began her work for the NCF as an assistant in the organisation’s publications department. [15] In May 1918 she was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment for refusing to pay a £60 (£3000 in today’s money) fine imposed on her for publishing an article by Bertrand Russell in which he had expressed the opinion that US troops garrisoned in Britain ‘will no doubt be capable of intimidating strikers, an occupation to which the American Army is accustomed at home’. [16] In 1920 she served a second term of imprisonment, this time for 21 days, for having published the Tribunal ‘without a legal imprint’.

A teacher from a Quaker background [17], Lydia Smith was prosecuted alongside Violet Tillard in May 1918 for refusing to divulge the name and address of the printer of the March issue of the NCF News, a private document issued to members of the NCF. However, the charges against her were dismissed under the Probation of Offenders Act. Unbeknowst to the authorities she was actually the Tribunal‘s editor. You can watch Lydia Smith talking on Yesterday’s Witness on the BBC South Today website ( she appears a 1.41, 7,32 and 11.58).

ENDNOTES

[1] ‘Prisoners of Conscience: No to the State’, Yesterday’s Witness, first broadcast 26 May 1969, available online at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01t27mf.

[2] ‘Joan Beauchamp – Printer’, Tribunal, 29 August 1918.

[3] Unless otherwise stated, material on the 11 April 1918 raid and subsequent prosecutions is drawn from the following sources: ‘Here we again!!’, Tribunal, 25 April 1918; ‘At Bow Street Again’, Tribunal, 16 May 1918; ‘Violet Tillard’, Tribunal, 15 August 1918; ‘Joan Beauchamp – Printer’, Tribunal, 29 August 1918; ‘Our Appeal’, Tribunal, 17 October 1918; ‘Rex v. Beauchamp’, Tribunal, 8 January 1920.

[4] We are grateful to Bill Hetherington for this information!

[5] William Chamberlain, Fighting for Peace: The Story of the War Resistance Movement, Garland, 1971, p. 70.

[6] Brock Millman, Managing Domestic Dissent in First World War Britain, Frank Cass, 2000, p. 83.

[7] David Boulton, Objection Overruled, MacGibbon & Kee, 1967, p. 271.

[8] Thomas C. Kennedy, The Hound of Conscience: A History of the No-Conscription Fellowship, 1914 – 1918, p. 249. According to F.L. Carsten, following the April 1918 raid the Tribunal ‘was henceforth printed in a wooden hut or barn on an estate at Box Hill in Surrey and taken from there to London’ (F.L. Carsten, War Against War: British and German Radical Movements in the First World War, Batsford, 1982, p. 205).

[9] Adam Hochschild, To End All Wars: How the First World War Divided Britain, MacMillan, 2011, p. 325. Variants of this story occur in Boulton (ibid.), who has the proof sheets ‘smuggled out of the office in the shawls of a baby’, and David Mitchell’s Women on the Warpath (Jonathan Cape, 1966, p. 342), where the conduit is the compositor’s grandmother ‘leading a young child and carrying a knitting bag’.

[10] See note 1 above.

[11] Anne Wiltsher, Most Dangerous Women: Feminist Peace Campaigners of the Great War, Pandora, 1985, pp. 4, 63, 131.

[12] Ibid., p. 66; Boulton, op. cit., p. 267.

[13] Wiltsher, op. cit.

[14] Wiltsher, op. cit., p. 145.

[15] Mitchell, op. cit., p. 339.

[16] Boulton, op. cit., pp. 268 – 269; Jo Vellacott, Bertrand Russell and the Pacifists in the First World War, Palgrave MacMillan, 1981, pp. 235 – 236; Kennedy, op. cit., p. 245.

[17] Mitchell, op. cit., p. 338.