Quite what Selina Cooper and her daughter Mary thought when, on 11 August 1917, their 1,200-strong demonstration demanding ‘a people’s peace’ [1] arrived at Nelson’s recreation ground to find a 15,000-strong patriotic mob already there, ‘baying for blood and hurling earth and clinkers’ [2], history has not recorded.

The demonstration was part of the Women’s Peace Crusade: the remarkable ‘grass-roots socialist movement’, pressing for peace negotiations to end the war, that ‘spread like wildfire across the country’ from the summer of 1917 until the Armistice the following year [3].

Denounced by the right-wing Morning Post as ‘one of the most active and pernicious propaganda organisations in the country’ [4], the Crusade’s aim, notes historian Jill Liddington, ‘was not genteel lobbying but persuading thousands of women out of their houses and on to the streets for popular open-air rallies to confront the militarist government’ [5].

‘Peace Our Hope’

Earlier that day, roughly 1,200 women and girls had assembled ‘in an open space a little distance from the centre’ of Nelson, a small Lancashire town of about 40,000 people [6].

Earlier that day, roughly 1,200 women and girls had assembled ‘in an open space a little distance from the centre’ of Nelson, a small Lancashire town of about 40,000 people [6].

A band had been engaged to accompany the procession but, ominously, on the eve of the demo the organisers were informed that there would be no music: the band’s committee would not allow it to play for ‘peace’.

Presumably anticipating trouble [7], organisers Selina Cooper and Gertrude Ingham, had placed themselves at the front of the march. At 52, Cooper was a long-term feminist and socialist from the town. Ingham’s son had been imprisoned as a Consientious Objector [8].

Behind them stood the members of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) Girl’s Guild, carrying a green banner bearing the words ‘Peace Our Hope’ in pale blue lettering. In front, a line of mounted police.

Other banners that day read ‘We demand a people’s peace’, ‘Workers of the world unite for Peace’ and ‘Hail the Russian Revolution’. A group of children, their fathers serving in the war, carried one saying simply: ‘We want our daddy’.

‘Pandemonium let loose’

Though the marchers received some support en route (‘Carry on, girls’), the crowd lining the route appears to have been largely hostile:

‘Traitors! Murderers!’ someone shouted, and women in the crowd tried to grab at the clothes of girls holding the banners. The booing and jeering grew louder and scuffling broke out. It was, as the nervous newspaper reporter covering the proceeedings admitted, ‘pandemonium let loose’. [9]

And, when they finally arrived at the recreation ground, there was the ‘vast throng’ of counter-demonstrators ‘stretching as far as the eye could see’.

Howled down by the mob – and with only the police presence preventing the speakers from being physically attacked – the rally lasted only forty minutes.

‘Something heroic’

A fortnight later, Selina Cooper told a meeting at the local school hall [10]:

‘I think that those who took part in the procession did something wonderful. It is one thing to come to a meeting like this; it is another thing to march through the street to be jeered and booed at. We will never forget that demonstration; I think it was something heroic … When the settlement comes, every woman who joined the crusade will be glad to be able to say, “I joined the peace crusade”.’

Her house was later raided by the police, searching for seditious literature [11].

The Women’s Peace Crusade

The Women’s Peace Crusade was ‘[t]he first truly popular campaign [in Britain], linking feminism and anti-militarism’ [12]. It’s central demand was ‘a people’s peace’: a negotiated end to the war without annexations or ‘crushing indemnities’ [13].

The Crusade began in Glasgow, where a 23 July 1916 demonstration by the ‘Women’s Peace Negotiations Crusade’ had drawn a crowd of 5,000.

Helen Crawfurd [14] – a working-class feminist and socialist who had played a significant role in the famous Glasgow Rent Strike of 1915 – had been galvanised into organising the protest by a letter in the Labour Leader complaining that ‘the Socialist women of Britain’ had not mounted ‘one public demonstration against this wholesale slaughter of our menfolk’.

Momentum was lost over the winter, but the idea of a women’s peace campaign calling for a negotiated end to the war took flight again in July 1917 after a second demonstration in Glasgow – using chalked adverts on the pavements to help spread the word – drew a crowd of between 12 – 14,000 men and women.

‘Shall we remain silent?’

In a June 1917 letter to the Labour Leader [15], Crawfurd pleaded:

‘For nearly three years the war has gone on, and we women have been afraid, afraid to trust our own judgement, afraid to speak, afraid to act. The ghastly slaughter of our sons, our husbands, our brothers has gone on and the spirit of fear has paralysed us. We believed our Government until it has been convicted so often of dishonesty that we are forced to think and act for ourselves … The people of Russia have appealed to the common people of every country to let their voices be heard demanding peace without annexations and without indemnities! They have called to us to subdue our Imperialists as they have vanquished theirs … It is to the Common People that the people of Russia have appealed. Shall we remain silent any longer?’

Her call was taken up and rallies, marches and demonstrations followed around the country: 3,000 attended a meeting in Leeds; 3,000 marched through Bradford; 300 marched in Birmingham (though their banner was torn up); and in Leicester a crowd of 3,000 assembled in the marketplace to listen to an all-woman platform of speakers [16].

123 branches

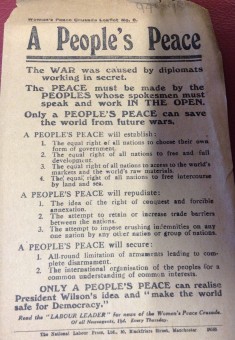

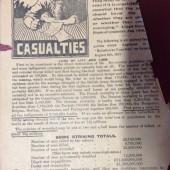

A Women’s Peace Crusade leaflet, possibly the same ‘Casualties’ that was distributed on the Salford-Manchester border after it was banned by Manchester police. Thanks to Ali Ronan for the image.

By 27 September 1917, a WPC ‘directory’ published in the Labour Leader (which devoted a regular space to the campaign) was able to list 33 branches. A year later this had grown to 123, seventy-seven of which are mentioned by name in Leader over the course of the WPC’s existence [17].

One WPC activist was arrested for picketing a church [18]. A second, a schoolteacher, was denounced in the pages of a national newspaper for wearing a WPC badge [19]. In Glasgow the WPC held anti-war meetings at the gates of the shipyards, and Helen Crawfurd and fellow activist Agnes Dollan got ‘into the Council Chambers while the Town Council was in session … showering down leaflets on the Councillors, demanding Peace and an end to the carnage’ [20]. In Manchester, police banned a WPC leaflet, ‘Casualties’, so activists travelled to the boundary with Salford (where the leaflet wasn’t banned) and leafleted Mancunians crossing the boundary [21].

Mobs and propaganda

The Crusaders faced government repression, mob violence and a massive government propaganda campaign.

By 1917 patriotic mobs had long become ‘one of the central mechanisms by which dissent was contained in wartime Britain’, with increasing elite and business involvement in their organisation as the war progressed [22]. In Manchester, a planned WPC demo was banned and women hustled from Stevenson Square ‘amid threats of violence’ [23], while a joint WPC-Women’s International League demonstration in Hyde Park was refused permission under the Defence of the Realm Act, ‘certain violence being apprehended’ [24].

By 1917 patriotic mobs had long become ‘one of the central mechanisms by which dissent was contained in wartime Britain’, with increasing elite and business involvement in their organisation as the war progressed [22]. In Manchester, a planned WPC demo was banned and women hustled from Stevenson Square ‘amid threats of violence’ [23], while a joint WPC-Women’s International League demonstration in Hyde Park was refused permission under the Defence of the Realm Act, ‘certain violence being apprehended’ [24].

Meanwhile, the National War Aims Committee (NWAC) – officially an NGO, in reality ‘almost totally funded by the Treasury’ – was flooding the country with pro-war propaganda, in an attempt to convince a war-weary nation of the necessity for ‘do[ing] all in its power to assist in carrying on the war to a victorious conclusion’ [25].

‘A people’s peace’?

Though it ultimately failed in its campaign for a negotiated end to the war ( ‘a people’s peace’), the WPC was the right campaign at the right time.

What with the March 1917 revolution in Russia, and the resulting call (referred to above by Crawfurd, sometimes referred to as the Stockholm Peace Conference proposal) for socialists to discuss peace terms over the heads of their respective governments; the July 1917 Reichstag Peace Resolution; the French Army mutinies of April – June 1917; the failure of Germany’s U-boat offensive to win the War; and the massive anti-war strike in Germany in January 1918, there were probably real possibilities for a negotiated peace in the winter of 1917 / 18 [26].

Moreover, Britain was a key obstacle to realising such a peace, a fact recognised not just by the anti-war Left.

In a November 1917 memorandum to the Secretary of State, Lord Lansdowne (a former Tory Foreign Secretary and a hawk at the war’s outbreak) noted his impression:

‘[T]hat the people of Germany and Austria would put irresistible pressure on their governments, and compel them to offer us decent terms, but for the success of those governments in convincing them that decent terms are unobtainable and that England is the sole obstacle in the way.’ [27]

In the teeth of business-funded patriotic mobs and a massive propaganda campaign bank-rolled by the Treasury, the odds were always heavily stacked against the Women’s Peace Crusade. That it was nonetheless, in Selina Cooper’s words, ‘something heroic’ cannot be denied.

NOTES

[1] ‘A People’s Peace’ (Women’s Peace Crusade Leaflet No. 6) spells out the terms of such a peace as follows:

A PEOPLE’S PEACE will establish:

1. The equal right of all nations to choose their own form of government.

2. The equal right of all nations to free and full development.

3. The equal right of all nations to access to the world’s markets and the world’s raw materials.

4. The equal right of all nations to free intercourse by land and sea.

A PEOPLE’S PEACE will repudiate:

1. The idea of the right of conquest and forcible annexation.

2. The attempt to retain or increase trade barriers between the nations.

3. The attempt to impose crushing indemnities on any one nation by any other nation or group of nations.

A PEOPLE’S PEACE will secure:

1. All-round limitation of armaments leading to complete disarmament.

2. The international organisation of the peoples for a common understanding of common interests.

(Capitals in original). A subsequent leaflet from 1918 (‘Lost Opportunities’, Women’s Peace Crusade Leaflet No. 8) declares the criminality of ‘neglect[ing] to examine fully every possible opening for ending the War on just and honourable terms’, listing 10 such openings (see note 20 below). Thanks to Ali Ronan for providing us with copies of these leaflets.

[2] Unless stated otherwise the following account of the Nelson demo is based on the following sources: Jill Liddington, The Long Road to Greenham, Virago, 1989, p.125; Jill Liddington, The Life and Times of a Respectable Rebel: Selina Cooper (1864 – 1946), pp. 277 – 280; Labour Leader, 16 August 1917.

[3] Long Road, pp. 117, 109.

[4] Labour Leader, 29 November 1917.

[5] Long Road, p. 117.

[6] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nelson,_Lancashire#Demography

[7] In late 1915, a patriotic mob led by a local cotton manufacturer had disrupted an anti-conscription meeting in Nelson. ‘Scuffling broke out. The chairwoman had to find refuge above the brawl by climbing on top of a piano’ (Life and Times, p.258). Typically, ‘The police arrived but chose not to intervene.’

[8] Life and Times, pp. 260-261, 275.

[9] Life and Times, pp. 277-278.

[10] Life and Times, pp. 279-280.

[11] Fortunately, she was tipped off by her daughter’s friend’s mother, who was the wife of the chief inspector in Nelson. Many years later, Mary (who was seventeen in 1917) recalled that four or five detectives had come and ‘searched every drawer … They even searched in the oven.’ Her mother hadn’t bothered to hide anything ‘because we hadn’t anything that they could find’ (Life and Times, pp. 281-282).

[12] Long Road, pp. 129.

[13] See note [1] above.

[14] After marrying a clergymen at 21, Crawfurd became a feminist and a socialist during her 20s. ‘When making the decision whether or not to go on the 1912 [Women’s Social and Political Union] raid, breaking windows down in Whitehall with seven other Scottish suffragettes, she prayed for a message from her husband’s sermon. It turned out to be about Christ making a whip of chords and chasing the money changers out of the temple, and she thought, “If Christ can be Militant so can I!”‘ (Anne Wiltshire, Most Dangerous Women: Feminist Peace Campaigners of the Great War, Pandora, 1985, pp. 148 – 149).

[15] Labour Leader, 21 June 1917. Emphasis in original.

[16] Long Road, pp. 124 – 126.

[17] Labour Leader, 12 September 1918. The seventy-seven named branches, whose names are reproduced in the poster, were: Aberdale, Aberdeen, Accrington, Annfield Plain, Barrow-in-Furness, Bath, Beaconsfield, Belfast, Birmingham, Blackburn, Bolton, Bradford, Brierfield, Bristol, Briton-Ferry, Brynmawr, Burnley, Burton-on-Trent, Carlisle, Clydebank, Colne, Corby, Coventry, Cowdenbeath, Cowling, Crosshills – Keighley, Cwmavon, Dalry, Darlington, Derby, Desborough, Douglas Water, Edinburgh, Exeter, Glasgow, Goole, Guildford, Halifax, Heanor, Huddersfield, Hull, Ilkley, Kendal, Kilmarnock, Leeds, Leicester, Liverpool, Lotherdale, London, Long Eaton, Manchester, Market Harborough, Merthyr Tydfil, Nelson, Netherfield, Newcastle, Newport, Northampton, Norwich, Nottingham, Paisley, Port Talbot, Reading, Rotherham, Rothwell, Sheffield, Shotley Bridge, Skelmanthorpe, Southport, Stanley, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Swadlincote, Troedyrhiw, Wakefield, Wellingborough, Wrexham, and Ystradgynlais. These branches are identified by name in the following issues of the Labour Leader: 6 Sept ’17; 27 Sept ’17; 4 Oct ’17; 18 Oct ’17; 25 Oct ’17; 1 Nov ’17; 15 Nov ’17; 13 Dec ’17; 29 Nov ’17; 24 Jan ’18; 7 Feb ’18; 28 Feb ’18; 14 March ’18; 11 April ’18; 25 April ’18; 2 May ’18; 16 May ’18; 30 May ’18; 27 June ’18; 18 July ’18; 25 July ’18.

[18] ‘The Peace Pickets on Sunday went to Christ Church distributing leaflets, and on the matter being reported to the verger, a special constable was sent for and the women arrested and taken to the Police Station, but not detained. Their banners however, were, and friends of peace are asked to help replace them by sending donations to Miss N.L. Smyth, 400, Old Ford Road, Bow, E3.’ (Labour Leader, 22 November 1917).

[19] ‘Mrs Crawfurd writes of a two-columned attack in the Sunday Post on a specially valuable teacher under the Glasgow School Board for wearing the purple and white button badge of the Women’s Peace Crusade during her school duties. As the paper published one of their best leaflets in full and set it beside a military parson’s fulmination against peace, and that after clearly stating the League’s aim to be to stop more bloodshed and to seek Peace by Negotiation, Mrs Crawfurd is inclined to rejoice rather than not.’ (Labour Leader, 8 November 1917). The purple-on-white badge – using two of the three suffragette colours and apparently featuring an ‘Angel of Peace protecting the children’ (Labour Leader, 21 June 1917) – was produced in Glasgow where Crawfurd, a former suffragette, was the leading figure in the Crusade. In September 1917, Ethel Snowdon – another leading figure in the Crusade – announced the creation of a second badge, this time red-on-white ie. using two of the three colours of the non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) (Long Road, p. 126). A prominent suffrage campaigner before the War, Snowdon had been a member of the NUWSS.

[20] Long Road, p. 128; Helen Crawfurd, unpublished Typescript Autobiography, p. 155.

[21] Long Road, p. 125.

[22] Brock Millman, Managing Dissent in First World War Britain, Frank Cass, 2000, p.99. In 1916, Britain’s former High Commissioner for South Africa, Alfred Milner, was ‘largely responsible for organising’ the British Worker’s National League (BWNL) – an ostensibly working-class, pro-war organisation (ibid., p. 112). Milner arranged funding for the group through Waldorf Astor (a Unionist MP and newspaper proprietor who became Lloyd George’s Parliamentary Private Secretary after the latter took power in December 1916) and the shipping magnate Sir James Knott. Funds were provided by the likes of the British Empire Producers Organisation and the British Sugar Growers Association (ibid., p. 115). ‘Given its reactionary – sometimes nearly hysterical – message, the violent nature of much of its membership, its acceptance of a corporatist social model, and its militaristic, chauvinistic programme, it is not difficult to see the BWNL as a proto-fascist organization’, Millman notes (ibid., p.118). Milner himself became a member of the five-person War Cabinet following Lloyd George’s December 1916 coup, and was later (from April 1918) Secretary of State for War.

[23] Long Road, p. 126.

[24] Millman, op.cit., p. 260.

[25] Ibid., pp. 233, 237. Formed in June 1917, the National War Aims Committee (NWAC)’s propaganda included films, speeches, leaflets, and photographic exhibitions. By 1918 it was ‘reaching something like six million people weekly’ (ibid., p.240). The NWAC was ‘almost totally funded by the Treasury, the Paymaster General handling its accounts directly as if it were an official department of state’ (ibid., p. 233). ‘In the year and a half of the NWAC’s existence, it received something like £1.2 million in subsidy or services from government sources’ (ibid., p. 234) – over £50 million in today’s money (http://www.measuringworth.com).

[26] This claim is argued forcefully in Douglas Newton, ‘The Lansdowne “Peace Letter” of 1917 and the Prospect of Peace by Negotiation with Germany’, Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 48, Number 1, 2002, pp. 16-39. The Women’s Peace Crusade Leaflet No. 8 (see note [1] above) cites both the Stockholm Peace Conference proposal and the Reichstag peace resolution in its list of ten ‘lost opportunities’ for peace.

[27] Ibid., p. 30.