The First World War was not inevitable. First, because an Anglo-German war was far from fated. Second, because, even during the July crisis of 1914, there were (untaken) opportunities to prevent it. And third, because Britain – whose participation was probably decisive in prolonging the conflict and turning it into a global war [2] – did not have to intervene at all. [3]

The wars that didn’t happen

Because the First and Second World Wars both pitted Germany against France, Britain, the US and Russia, these alignments have come to seem foreordained. In fact, ‘[i]n the years before 1914, there could have been a war over colonial issues between Britain and the United States, Britain and France, or Britain and Russia – and in each case there nearly was.’ [4]

Moreover, it cannot ‘be claimed that there were insuperable forces generating an ultimately lethal Anglo-German antagonism’: around the turn of the century an Anglo-German understanding ‘seemed not only desirable but possible’ to statesmen in both countries. [5]

Paths not taken

War remained evitable [6] once the July crisis had begun.

For example, the British Government could have conducted – and peace activists pushed for – ‘a credible, active diplomacy of mediation, strengthened by a commitment to strict neutrality and genuinely even-handed negotiation’. [7] It didn’t.

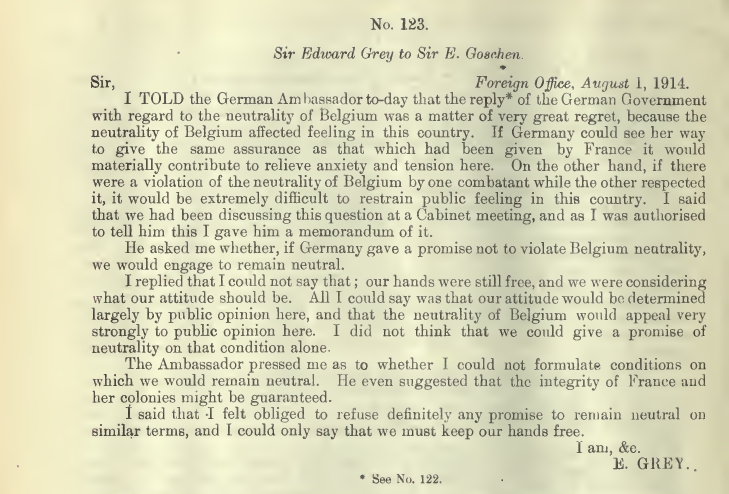

The infamous ‘Document 123’, reproduced in the British Government’s August 1914 ‘dodgy dossier’ justifying its decision to go to war: ‘Correspondence Respecting the European Crisis’.

Instead, Britain took a series of provocative moves – such as Churchill ‘order[ing] the First Fleet not to disperse after a test mobilisation’ and publicising this initative to the press – that compromised its ability to mediate, while at the same time doing ‘very little to restrain Russia’, whose ‘impatience to mobilise’ was a key factor in the crisis. [8]

Britain also rejected a series of German offers to exchange a British pledge of neutrality for German commitments: to make no annexations in Europe; to guarantee the integrity of France and her colonies; to respect Belgian neutrality; and not to use her naval forces against France. [9] It also rejected a German attempt to confine the war to Eastern Europe. [10]

Enormous changes at the last minute

The possibilties for averting disaster should not be underestimated.

On 1 August 1914, ‘even the whiff of a continuing possibility of British neutrality’ on 1 August 1914, led the German Emperor ‘to demand sweeping changes in the German war plan’, exasperating his generals and temporarily sparing both Belgium and France from invasion. [11]

Likewise, after receiving an ambiguous (and immediately ‘clarified’) telegram from the French on 30 July, urging Russia’s leaders to avoid ‘any measure which might offer Germany a pretext for a total or partial mobilisation of her forces’, the latter did briefly pause their preparations. [12]

What might have happened had Britain exerted itself for peace?

NOTES

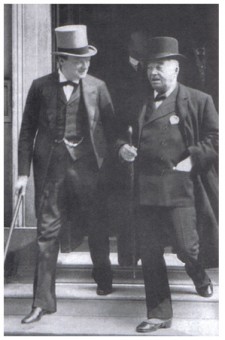

Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty and Lord Fisher, after a meeting of the Committee of Imperial Defence, 1913.

[1] Douglas Newton, Darkest Days: The Truth Behind Britain’s Rush to War, 1914, Verso, 2014, p. 51. Churchill, who was writing to his wife Clementine, went on to note that he ‘pray[ed] to God to forgive me for such fearful moods of levity. Yet I w[oul]d do my best for peace, & nothing w[oul]d induce me wrongfully to strike the first blow.’ In reality he did his best to ‘frogmarch events’ in the direction of war: encouraging the advocates of ‘firmness’ in Russia and France by first ‘order[ing] the First Fleet not to disperse after a test mobilisation’ and publicising this initative to the press, and then ordering it to move to its war stations on 28 July (both decisions taken behind the Cabinet’s back); and secretly making contact with leading Tories in order to help bring more pressure to bear on the Cabinet in favour of military intervention (ibid., pp. xx, 26-30, 50 – 54, 132). On 22 February 1915, Churchill told Asquith’s daughter Violet: ‘I think a curse should rest on me – because I love this war. I know it’s smashing & shattering the lives of thousands every moment – & yet – I can’t help it – I enjoy every second of it’ (Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War, Penguin, 1998, pp. 177 – 178). Churchill appears not to have had too much personal contact with the ‘smashing and shattering’ aspect of the war, even during the months in which he served at the Front. When he arrived to join his battalion near the Belgian border on 5 January 1916 he did so ‘accompanied by two grooms and a large limber containing all his personal belongings, which included his own bath and boiler’, and at lunch ‘refused to speak to his junior officers’ who he regarded as his social inferiors (Clive Ponting, Churchill, Sinclair-Stevenon, 1995, p. 200). His battalion moved forward on 24 January to ‘a quiet section of line’, where it lost 15 killed and 123 wounded in the next three months (ibid., p. 200 – 201). Churchill returned to civilian life shortly before it was sent to the slaughter at the Somme (ibid., p. 203). Tony Ashworth speculates that the relative lack of drama during Churchill’s frontline service may be the reason why Churchill – who wrote at length about the various colonial wars in which he had participated – wrote no memoirs of his time on the Western Front (Tony Ashworth, Trench Warfare, 1914 – 1918, The Live and Let Live System, Pan, 1980, p. 37).

[2] ‘From a Balkan and a continental conflict, Britain’s intervention began a further massive stage of escalation towards a world war. Almost certainly it prevented Germany from defeating France and Russia in a matter of months’ (David Stevenson, 1914 – 1918: The History of the First World War, Penguin, 2005, p. 32).

[3] The British cabinet almost collapsed on the eve of the war over the question of intervention, with four Cabinet ministers and one junior minister resigning on 2-3 August 1914, the former believing that ‘the Cabinet was being artfully drawn on step by step to war for the benefit of France and Russia’ (Newton, op. cit., 187, 194 – 201, 250). Ultimately, there was no democratic decision for war in Britain, with Parliament kept almost completely in the dark, and the Cabinet frequently sidelined. Indeed, Churchill later conceded that all of the ‘supreme decisions’ – to send an ‘ultimatum’, to declare war on Germany, to send the British Expeditionary Force to the continent – ‘were never taken at any Cabinet’ (Newton, op. cit., p. 240, 266, 300; see also Douglas Newton, ‘”This black horror of inconceivability”: Dissenters in British Foreign Policy and Britain’s Rush to War, July-August 1914’, p. 29 – 30 in Bernard Mees and Samuel P. Koehne, eds., Terror, War, Tradition: Studies in European History, Australian Humanities Press, Unley, South Australia, 2007, pp. 17-40).

[4] Margaret MacMillan, The War that Ended Peace: How Europe Abandoned Peace for the First World War, Profile Books, 2014, p. 55. In 1885 ‘an Anglo-Russian conflict threatened to break out following the Russian victory over Afghan forces at Penjdeh’ while during the period 1894 – 1905, Russia, not Germany, posed ‘the most significant long-term threat’ to British interests (Ferguson, op. cit., p. 41; Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, Penguin, 2013, p. 137). Elsewhere, the Fashoda Crisis had taken France and Britain ‘to the threshold of war’ in 1898, while a boundary dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana had led to ‘much excited talk of war in both Britain and the United States’ in 1895 (ibid., p. 132; MacMillan, op. cit., p. 41). It was imperial tensions between Britain and France and between Britain and Russia that led to the signing of the 1904 Entente Cordiale and the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention respectively (Clark, op. cit., pp. 139 – 140). Crucially, neither agreement ‘was conceived by British policy-makers primarily as an anti-German device’ – indeed, the transition to ‘a simpler cosmos in which one enemy [ie. Germany] dominated the scene’ was ‘not the cause … but rather [a] consequence’ of Britain’s alignment with Russia and France, with British foreign policy ‘depend[ing] on scenarios of threat and invasion as focusing devices’ (ibid., pp. 140, 166).

[5] Ferguson, op. cit., pp. 45, 49. Kept secret from the public, one of Britain’s ‘two reasons’ for fighting the war was ‘to secure a peace settlement which would enhance the security of Britain and its empire against not just its enemies, but also against its allies’ (David French, The Strategy of the Lloyd George Coalition, 1916 – 1918, p. 3). Indeed, British policy makers originally planned to let the other Great Powers – allies and enemies alike – bleed each other dry so that an essentially unbloodied Britain could then step in and ‘grasp the lion’s share of the spoils … dictat[ing] terms not just to their enemies but also to their allies’. (ibid., p. 4) To this end their ‘initial goal was to render just sufficient assistance to Britain’s continental allies to prevent them from collapsing’, in the expectation that ‘by late 1916 the land forces of all of the continental belligerents would be exhausted’. (ibid., pp. 3 – 4).

[6] Though rarely used, the OED lists ‘evitable’ as a word recorded in 1502 (Daniel Dennett, Freedom Evolves, Penguin, 2003, p. 56).

[7] Newton, op. cit., p. 300.

[8] Newton, op. cit., pp. 27 – 29, 300; MacMillan, op. cit., p. xxxi. On 25 July 194 – the date Russia decided to begin its ‘Period Preparatory to War’ on the German and Austrian fronts, a decision that Russia’s military elite regarded ‘as a green light for war’ – British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey’s key Foreign Office adviser, Eyre Crowe told him that ‘The moment has passed when it might have been possible to enlist French support in an effort to hold back Russia’, advising him against ‘any representation at St Petersburg and Paris’ (Newton, op. cit., pp. 21, 296). Of course, there is no shortage of blame to be spread around and ‘aristocratic incompetents and imperial fantasists … stalked the gilded rooms of power across Europe’ (ibid., p. xxiii). In addition to Germany’s infamous ‘blank cheque’ to Austria-Hungary, France ‘exercised no brake upon Russia’ (effectively giving it a blank cheque), while Sean McMeekin has argued that Russia, perceiving ‘a moment that seemed uniquely propitious for enlisting British and French power to neutralize the mounting German threat to Russia’s ambitions … plunged Europe into the greatest catastrophe of modern times’ in pursuit of Constantinople and the Bosphorus (Clark, op. cit., p. 414 – 415; Newton, op. cit., p. 29; Sean McMeekin, The Russian Origins of the First World War, Harvard University Press, 2013, pp. 232 – 233).

[9] Douglas Newton, Darkest Days: The Truth Behind Britain’s Rush to War, 1914, Verso, 2014, pp. 84, 141, 221, 357 n.23.

[10] Ibid., p. 150.

[11] Ibid., p. 152.

[12] Newton, op. cit., pp. 303 – 304. The telegram had also asserted that ‘France [wa]s resolved to fulfil all the obligations of the alliance’. However, on instructions from the French President, the telegram was immediately ‘clarified’ to Russia’s ambassador in France, who then reported the additional assurances that France had ‘no wish to intervene in [Russia’s] military preparations’ and that the French Minister of War believed that a temporary slowing of Russia’s mobilisation ‘need not prevent [Russia] … from continuing [its] military preparations and indeed pursuing them more energetically, as long as we refrain from mass transports of troops’ (Clark, op. cit., p. 505 – 506). The French telegram, Clark explains, was not really an attempt to restrain Russia, but instead part of ‘the complex triangulations of a French policy that had to mediate between the hard imperatives of the Franco-Russian Alliance and the fuzzy logic of the Anglo-French Entente’ (ibid.).