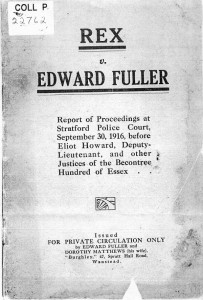

On 30 September 1916, peace activist Edward Fuller was prosecuted at Stratford Magistrates Court. His crime? Requesting a quote to have a poster, featuring the words of government lawyer Archibald Bodkin, exhibited in various parts of East London. The prosecutor in his case? Archibald Bodkin.

The poster had been produced by the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF). One of the main anti-war organisations in Britain during the First World War, the NCF provided support to those refusing conscription, over 6,000 of whom were jailed, often under harsh conditions. [2]

Described by his lawyer as ‘a follower of Tolstoy’, Edward Fuller was a journalist and a member of the Forest Gate branch of the NCF. [3]

Conscription (for single men between the ages of 18 and 40) passed into law in Britain on 27 January 1916, and on 17 May 1916 eight members of the NCF’s national committee were convicted and fined £100 each for printing a leaflet, Repeal the Act, calling for an end to conscription. [4]

An unwitting ‘pacifist speech’

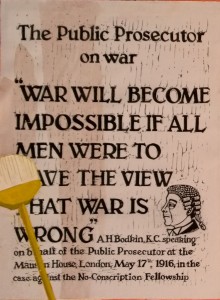

During the trial the prosecutor, Crown Advocate [5] Archibald Bodkin, read out the following passage from the Repeal the Act leaflet:

War, which to us is wrong, war, which the peoples do not seek, will only be made impossible when men who so believe remain steadfast to their convictions

and commented himself that ‘War will become impossible if all men were to have the view that war is wrong’. [6]

Believing that Bodkin had ‘kindly provided us with such a terse and explicit phrase, expressing our view regarding war’ the NCF mischievously turned Bodkin’s unwitting ‘pacifist speech’ into a poster, and had copies printed by the National Labour Press. [7]

‘A quotation for exhibiting posters’

On 27 (or possibly 28) August 1916 Mr A.E. Abrahams, managing director of the Borough Theatre Billposting Company Ltd in Romford Road, Stratford, received a letter from Fuller asking for ‘a quotation for exhibiting posters, similar to the enclosed, on hoardings in Stratford, Forest Gate, Ilford, Leytonstone, Wanstead and Woodford … from 50 [posters] upwards’.

He replied on 28 August with the quote (10s per hundred), asking Fuller ‘if you have received the consent of the War Office to have this bill exhibited.’ At the same time he sent the poster to the War Office.

Two days later, on 30 August, Fuller replied:

‘I do not think you need entertain the least doubt as to their legality. The poster is a verbatim report of a remark made by Crown Counsel in the course of a speech in a recent legal action, and in various forms has been published broadcast throughout the country, without any successful action [8] being brought against the publishers under the Defence of the Realm Regulations, or otherwise’.

He went on to note that, since he would be ‘sorry to implicate you in any proceedings … doubtless you will be able to obtain the assurance of the War Department that no liability would attach to you’.

Abrahams in turn replied, saying that he had contacted the authorities and was waiting to hear back from the War Office.

A detective calls

Having heard nothing more from him, Fuller then sent a third letter, dated 11 September, asking Abrahams if the War Office had responded. However this letter never reached Abrahams. Instead, it was opened by Abraham’s secretary Hilda Bailey, who was instructed not to answer it by ‘a representative from Scotland Yard’.

Twelve days later, on 23 September, Detective Sergeant Edward Pittaway arrived at Fuller’s house to issue him with a summons.

Fuller was to be prosecuted for unlawfully attempting (and doing) an act prepatory to making ‘in print, statements likely to prejudice recruiting, discipline, and administration of his Majesty’s military forces’ – an act prohibited by the draconian Defence of the Realm (Consolidation) Regulations, 1914. [9]

‘It is a platitude’

During the trial, Bodkin called Brigadier-General B.E.W. Childs – then a senior military official from the War Office – to give his assessment of the likely impact of the poster on recruiting. [10]

Cross-examined by Fuller’s lawyer, R.C. Hawkin, Childs conceded:

I agree that war would be impossible if all men were to have the view that war is wrong. I agree that that is a perfectly true statement. It is a platitude.

Hawkin questioned whether Fuller:

Ought … to be dug out of his home and brought up to the magistrates because he wrote a letter asking a billposter to be kind enough to give him a quotation for posting the words of the Public Prosecutor at a public trial?

asking:

Why is not every clergyman in the land prosecuted because, every Sunday, he says “Give Peace in our time, O Lord,” and Mr Bodkin and General Childs, and I, and all of us, reply, “Because there is none other that fighteth for us, but only Thou, Oh God”?

A mischievous remark

He also suggested that:

In this case the proper course, the correct course, was to have sent a constable, not to Miss Bailey, but to Mr Fuller, to say: “Look here: the War Office takes the view that Mr Bodkin has made a mischievous remark, and that his words might prejudice recruiting. We all know Mr Bodkin, but we all think that these particular words have an unfortunate smack.”

Nevertheless, Fuller was convicted and fined £100 – over £5,500 in today’s money [11] – or 91 days imprisonment. He was also ordered to pay £21 costs. He was imprisoned, though according to Sylvia Pankhurst ‘owing to Parliamentary protests on his behalf, he was released before the sentence was fully served’. [12]

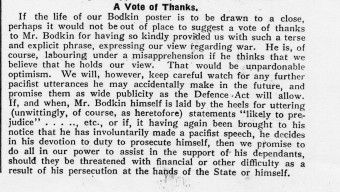

A vote of thanks

However, as a result of the case, the text of the Bodkin poster was widely reproduced verbatim in both the local and national press, including in the Daily Telegraph, The Weekly Dispatch, The Manchester Dispatch and the Essex County Chronicle – reaching vastly more people than would ever have seen the original posters.

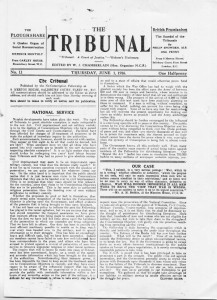

In its weekly newspaper The Tribunal, the NCF noted, wryly, that:

If, and when, Mr Bodkin himself is laid by the heels for uttering (unwittingly, of course, as heretofore) statements “likely to prejudice” …., etc., or if, it having again been brought to his notice that he has involuntarily made a pacifist speech, he decides in his devotion to duty to prosecute himself, then we promise to do all in our power to assist in the support of his dependants, should they be threatened with financial or other difficulty as a result of his persecution at the hands of the State or himself. [13]

The Tribunal generously offers to support Bodkin’s dependants if he should feel it necessary to prosecute himself …

ENDNOTES

[1] Edward Fuller and Dorothy Matthews, Rex v. Edward Fuller : Report of Proceedings at Stratford Police Court, September 30, 1916, before Eliot Howard, Deputy-Lieutenant, and other Justices of the Becontree Hundred of Essex, privately circulated, date unknown, p. 19.

The 1 June 1916 edition of The Tribunal, containing the Bodkin quote (‘Our Case’) on its front cover.

[2] Adam Hochschild, To End All Wars: How the First World War Divided Britain, MacMillan, 2011, p. xvi.

[3] Unless otherwise sourced, all details about the case are drawn from Fuller et al, op. cit.

[4] Sarah Tudor, ‘Britain and the First World War: Parliament, Empire and Commemoration’, House of Lords Library Note, 24 March 2014, p. 11; Thomas C. Kennedy, The Hound of Conscience: A History of the No-Conscription Fellowship, 1914 – 1919, University of Arkansas Press, p. 127.

[5] The poster mistakenly refers to Bodkin as both ‘The Public Prosecutor’ and a K.C (King’s Counsel). As was conceded by Fuller’s lawyer at the trial, neither description was correct. Bodkin was a Crown Advocate at the time of the May 1916 Repeal the Act prosecution, though he did later become the Director of Public Prosecutions, in which capacity he infamously interceded to have James Joyce’s Ulysses banned.

[6] Bodkin appears to have believed that he was merely restating the excerpt from the Repeal the Act leaflet. In fact the two statements have entirely different meanings. The excerpt said that a necessary condition for war to become impossible was that those men who didn’t believe in war not fight; Bodkin’s statement, on the other hand, says that a sufficient condition for war to become impossible is for all men to come to the opinion that war is wrong. Bodkin really was, therefore, the sole author of the statement printed on the NCF poster!

[7] ‘The Bodkin Poster’, Tribunal, 5 October 1916.

[8] At least four other people were charged in relation to Bodkin’s involuntary ‘pacifist speech’. In July 1916, Thomas John Williams of Pritchard Street, Tonyrefail (South Wales) was charged under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) ‘with having under his control certain documents containing statements the publication of which would be likely to prejudice recruiting’ (‘South Wales Police Object to Mr Bodkin’s Speech!’, Tribunal, 13 July 1916). The documents in question were copies of the Tribunal, the offending section of which reproduced the Bodkin quote under the heading ‘Our Case’. His sister and two school-boys were also charged with distributing the papers. However, according to a report in the Tribunal, ‘The Stipendiary [magistrate] upheld the [defence’s] objection [that the paper did not fall under relevant DORA regulations] and dismissed the case against [Mr] Williams … reserv[ing] his decision in the other three cases.’

[9] Specifically, Fuller was prosecuted using Regulations 27 and 48, passed under the Defence of the Realm (Consolidation) Act, 1914.

[10] Unbeknownst to the NCF, Childs was probably jointly responsible, alongside Sir Nevil Macready, for having several dozen conscientious objectors shipped to France earlier that year with a view to having them sentenced to death (Will Ellsworth-Jones, We Will Not Fight …, Aurum, 2008, pp. 173, 198 – 203).

[11] See http://www.measuringworth.com/ukcompare/

[12] E. Sylvia Pankhurst, The Home Front: A Mirror to England During the First World War, The Cresset Library, 1987, p. 329.

[13] ‘A Vote of Thanks’, Tribunal, 5 October 1916.