There were already police informers at the dance-hall so they decamped to a pub in Sophienstrasse. [3]

There were already police informers at the dance-hall so they decamped to a pub in Sophienstrasse. [3]

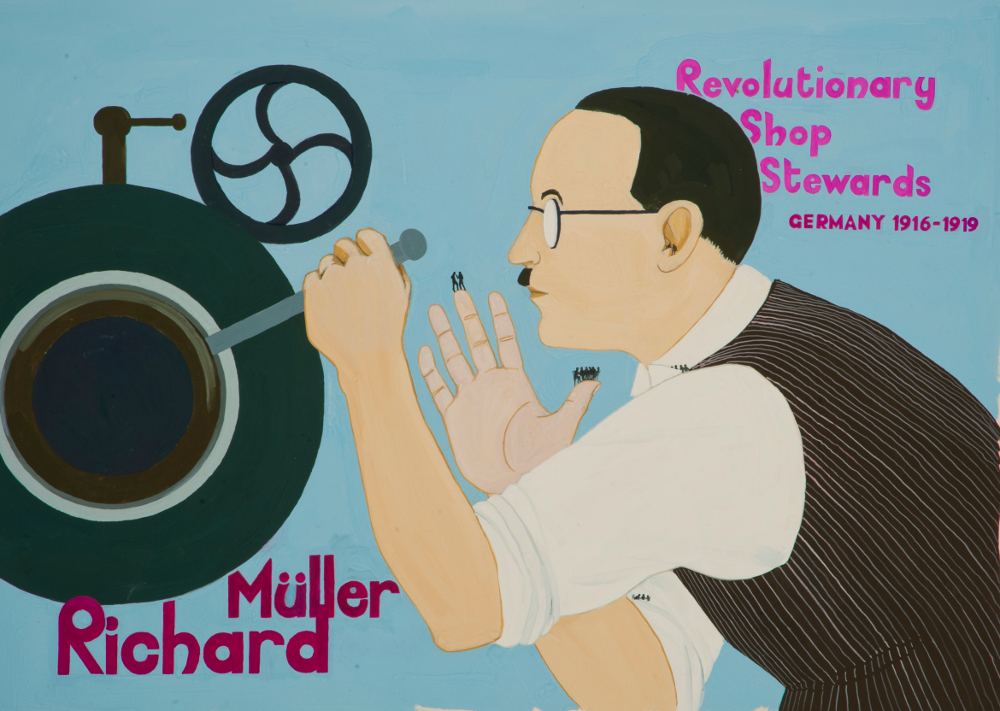

There, a man with thick round glasses and a toothbrush moustache proposed that they take action the following day, when Karl Liebknecht – Germany’s most famous anti-war campaigner – would be on trial for treason after denouncing the war and the government at a May Day demonstration [4].

The proposal was agreed and the group of roughly thirty men [5] dispersed to spread the word.

The next day, some 55,000 workers left their workplaces to march in perfect discipline through the streets of Berlin. [6] Munitions workers from roughly forty Berlin armament works they shouted ‘Long live Liebknecht!’ and ‘Long live peace!’. [7] Meanwhile, two hundred kilometers to the west, an estimated three-fifths of the workforce in some 65 factories in Brunswick also joined the strike. [8]

In the next 2½ years the man with the toothbrush moustache would organise two more anti-war strikes, each bigger than the last, be conscripted into the army three times, and play a leading role in the overthrow of the centuries-old Hohenzollern dynasty. For a few weeks he would even, albeit briefly, become the German head of state. [9]

The date of Liebknecht’s trial – and of the munitions workers strike – was 28 June 1916, and the man with the interesting times ahead of him was Richard Müller, leader of a clandestine network within the German Metalworkers Union (DMV) that would later [10] call itself the Revolutionary Shop Stewards.

250 demos, 163 cities

The days leading up to the war had seen over 250 peace demonstrations take place in 163 cities and towns across Germany. Some three quarters of a million people had taken part, many of them members of the socialist Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). [11]

The days leading up to the war had seen over 250 peace demonstrations take place in 163 cities and towns across Germany. Some three quarters of a million people had taken part, many of them members of the socialist Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). [11]

The biggest party in the German Parliament, the SPD had received over 4 ¼ million votes – a third of the electorate – in the 1912 election, and had traditionally ‘proclaimed [its] opposition to war from the rooftops’, even voting against the budget because it sanctioned Germany’s vast military expenditure. [12]

On 31 July 1914 the SPD’s leadership sent a representative to Paris to speak directly to the French socialist leaders. There, the next day, he told them ‘several times over’ that the SPD’s delegates would not vote in favour of war credits in the German Parliament. [13]

However, as soon as the war began, the SPD rapidly ditched its socialist internationalism: supporting the war effort, voting for war credits on 4 August 1914, and agreeing a political truce with the government for the duration of the war. [14]

The major unions were also part of this Burgfrieden (lit. ‘peace of the castle’) ‘call[ing] off all ongoing strikes and [deciding] not to initiate any new labour actions’. [15]

‘Treason towards the international’

Needless to say, not everyone was happy with these developments.

Needless to say, not everyone was happy with these developments.

Within a month of the war credits vote, Karl Liebknecht had branded his decision to follow party discipline as ‘treason towards the International’, declaring ‘that he could not himself understand what possessed him when he gave his vote’. [16]

A lawyer and a socialist, Liebknecht had been jailed for high treason in 1907 after publishing a book entitled Militarism & Anti-Militarism. [17] At the war’s outbreak he was not only a Deputy in the German Parliament (Reichstag), but also an assemblyman in the Prussian Parliament (Landtag) and a Councilman on the Berlin City Council! [18] A left-wing journalist who knew him described him as possessing ‘an intensity of feeling with the victims of any tyranny which made him ready to make any, really any, sacrifice …’ [19]

In September 1914 he travelled to Belgium, returning ‘convinced that the Belgians … had not organised bands of [guerillas], that they had not assassinated the German wounded, and that the German executions in Belgium were unjustifiable’. [20] In December he became the first SPD delegate to vote against further war credits. [21] The following March he was conscripted, and he was injured at the Front in October 1915. [22]

In January 1916, he was expelled from the SPD after asking questions about the Armenian genocide and German atrocities in Belgium in the Reichstag. [23]

Resisting the Burgfrieden

In the meantime, opposition to the Burgfrieden was also being secretly organised inside the German Metalworkers Union (DMV), the largest trade union in the world. [24]

In the meantime, opposition to the Burgfrieden was also being secretly organised inside the German Metalworkers Union (DMV), the largest trade union in the world. [24]

It started in Berlin, ‘where the lathe operators organised allegedly apolitical pub evenings or met privately after the official union sessions – sessions that were often infiltrated by the police or at least dominated by patriotic unionists’. [25] Each Steward ‘represented an entire job site or plant where he in turn had trusted representatives in various departments and shops within it’. [26]

Gradually they built a covert network within the union, capable of bringing tens of thousands of workers out on strike for political purposes during the war – something that none of the other left-wing opposition groups in Germany was ever able to do. [27]

Their political leader, Richard Müller, was the head of the lathe operators section of the Berlin Branch of the DMV and ‘one of the few leaders of the working class movement [in Germany] who was himself a worker, hailing from obscurity and poverty’. [28] By the time he was 15 both of his parents had died, and he probably had no formal education beyond eight years of primary school. [29]

They didn’t start as radicals [30] – indeed, the lathing shops ‘were central to arms production’ [31] – but were instead initially animated by a common desire not to jettison their only means of exerting pressure on their employers: the strike. [32] However, as the war progressed they became increasingly radicalised. The June 1916 strike in solidarity with Liebknecht would mark a key turning point in this development. [33]

‘We will have peace – now!’

On 1 May 1916 four of Karl Liebknecht’s comrades called, very early, at his home at 14 Hortensienstrasse. Liebknecht’s face was ‘deathly pale’, and his grim silence spoke volumes: his visitors realised that he was about ‘to hurl prudence to the four winds and defy the Government’. [34]

On 1 May 1916 four of Karl Liebknecht’s comrades called, very early, at his home at 14 Hortensienstrasse. Liebknecht’s face was ‘deathly pale’, and his grim silence spoke volumes: his visitors realised that he was about ‘to hurl prudence to the four winds and defy the Government’. [34]

A primitive flier was distributed, stating simply: ‘Whoever is against the war, assemble on 1 May at 8 o’clock in the evening at Potsdamer Platz (Berlin). Bread! Freedom! Peace!’ [35]

Thousands came, though according to one account they were ‘mostly women’ and ‘more children in the crowds than men and women together’. [36] The police were also there in full force.

Standing on either a raised platform or a car, with Rosa Luxemburg at his side, Liebknecht spoke to the assembed throng, telling them that:

‘By a lie the German workingman was forced into the war, and by like lies they expect to induce him to go on with war!’ [37]

Amidst shouts of ‘Hurrah for Liebknecht!’, he raised his hand for silence, telling them: ‘Do not shout for me, shout rather “We will have no more war. We will have peace – now!”‘ [38] As the police moved in to disperse the crowd, he shouted ‘Down with the war! Down with the government!’, and was immediately arrested.’ [39]

The metalworkers walkout on the day of Liebknecht’s trial was the first political mass strike of the war to take place in Germany. [40] It would not be the last. [41]

Three strikes

Dozens of striking workers and suspected leaders, including Müller, were drafted and sent to the Front following the June 1916 strike – though Müller was discharged after only three months. [42] Nevertheless, the action had transformed a demonstration of state power into a show of strength for the anti-war movement and demonstrated the Stewards’ ability to bring tens of thousands of workers out of their workplaces and onto the streets. [43]

Dozens of striking workers and suspected leaders, including Müller, were drafted and sent to the Front following the June 1916 strike – though Müller was discharged after only three months. [42] Nevertheless, the action had transformed a demonstration of state power into a show of strength for the anti-war movement and demonstrated the Stewards’ ability to bring tens of thousands of workers out of their workplaces and onto the streets. [43]

Typically, the Spartacists – the revolutionary socialist grouping associated with Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg – immediately tried to organise a follow-up strike, but – just as typically – the Stewards resisted these calls, judging that ‘the mood in their working-class communities [would be] unreceptive’. [44]

Instead, the next mass strike took place in April 1917, and this time involved as many as 300,000 people from over 300 armaments works in Berlin, many of them women, as well as simultaneous strikes in Halle, Magdeburg and Leipzig. [45] Its political demands would eventually include peace without annexations, universal equal voting rights with a secret ballot, and the release of Richard Müller, who had been arrested again and sent to a military camp two days before the strike began. [46]

A third strike, involving ½ million people, followed in January 1918. From the outset its demands included the ‘lifting of the state of siege and of the militarisation of the factories, the freeing of political prisoners, freedom of speech and the press … and the speedy conclusion of peace “according to the provisions formulated by the Russian people’s commissars at Brest-Litvosk”‘. [47] ‘A strike of such magnitude had never been seen in Germany before, let alone during wartime’. [48]

Hundreds of strikers were rounded up and conscripted into the army, martial law imposed, and the Berlin Military District announced that it would be ‘a military offence for strikers not to report to work on the morning of February 4 [1918]’. [49] Fearing a massacre by the still-loyal army, the Stewards ended the strike on 3 February.[50]

In its wake an estimated 50,000 strikers were sent to the front, and Müller was drafted for a third time. [51] But the Stewards had prepared for this repression – each naming a substitute who could replace them in the event of a mass arrest. – and would later begin stockpiling weapons for an armed revolt. [52]

However, it was not the workers but the sailors who would begin the German Revolution.

‘For us the war is over’

Germany’s revolution ‘resulted directly from Germany’s armistice request and the [Allied] invasion threat after Austria-Hungary collapsed’, and was therefore an outcome, rather than a cause, of Germany’s military defeat. [53]

At the end of October 1918, with negotiations on the terms of the armistice continuing, the German admiralty – acting on its own initiative – ordered one last desperate attack on the British Navy. [54]

Though it would have jeopardized the negotiations, this attack ‘could not have exercised any influence on the outcome of the war’. [55] It never took place.

Instead the sailors at Willhelmshaven mutinied. Some ships went to the rendezvous point as ordered, but upon arrival the sailors extinguished the fires in the boilers and refused to proceed. Other ships never even weighed anchor. Challenged by their officers the mutineers replied: ‘We do not put to sea, for us the war is over’. [56]

The mutiny led to a revolt in Kiel, a radical centre that had supported the January 1918 strike, which in turn set off a series of virtually bloodless uprisings throughout Germany. [57] Inspired by the Russian example, workers and soldiers around the country formed thousands of councils. [58]

‘Class cancelled because of revolution’ [59]

Finally, on 9 November 1918, the revolution came to Berlin.

Finally, on 9 November 1918, the revolution came to Berlin.

An ‘astonishingly bloodless’ affair, this was organised by the Stewards, whose ‘systematic preparation for the uprising’ was critical, even though on the day itself ‘most of the actions were in fact uncoordinated, spontaneous and improvised’. [60]

The night before, Müller – who ‘had not been home or seen his family for weeks out of fear that he would be followed by the police and military’ – watched as heavily armed soldiers marched by him in endless rows. Convinced that these men would ‘drown the people’s revolution in blood’ he felt ‘shamefully small and weak’. [61]

But the next day the workers carried red flags and placards addressed to the garrison troops saying ‘Brothers, no shooting!’, and ‘hardly a soldier was prepared to fire on them’. [62]

‘I hate it like sin’

The overthrow of the monarchy – followed by the signing of the armistice two days later – ushered in a new struggle, this time pitting revolutionaries like Liebknecht, Müller and Luxemburg (all of whom had opposed the war) against the SPD’s leadership, who had supported the war and now chose to collaborate with ‘the most reactionary sections of German society, the officer corps and the state bureaucracy’, in order to prevent more revolutionary change. [63]

On 9 November, the SPD’s chairman, Friedrich Ebert, was made Chancellor. That evening Ludendorff’s successor General Wilhelm Groener rang to tell him that the officer corps expected the new government to ‘fight against Bolshevism and places itself at the disposal of the government for such a purpose’. [64]

Ebert, who only two days earlier had told his predecessor Prince Max of Baden, that he hated revolution ‘like sin’, would have no problem with this. [65]

The revolutionaries’ hopes were ultimately crushed using massive violence [66], though the fetishisation of armed struggle probably also contributed to their failure. [67]

However, even more fundamental was the reality that, while ‘[d]emands for the democratisation of the postwar army and the socialisation of key industries’ were shared by a significant proportion (perhaps even a majority) of the German working class, there was also a false expectation that such change ‘would be executed from above by a benevolent government’. [68]

‘Germany became a democracy – but a democracy in which the bastions of power were held by the adherents of the old regime. It was the generals and the bureaucrats, the agrarians and the industrialists, who dominated the fate of the first German republic … [until] finally they succeeded in destroying it by handing over political power to [Hitler]’. [69]

ENDNOTES

[1] Ernst Däumig, ‘The National Assembly Means the Councils’ Death’, p. 42 in Gabriel Kuhn (ed), All Power to the Councils! A Documentary History of the German Revolution of 1918 – 1919, PM Press, 2012. A former soldier, Däumig lost his job as editor of the SPD’s newspaper Vörwarts because of his opposition to the war, joining the Stewards in the summer of 1918 (Ralf Hoffrogge, Working-Class Politics in the German Revolution: Richard Müller, the Revolutionary Shop Stewards and the Origins of the Council Movement, Brill, 2014 [hereafter, ‘Hoffrogge 1’], p. 57).

[2] Hoffrogge 1, p. 90. Kuhn, op. cit., p. 31.

[3] Ibid., p.37. The group had booked the Musiker-Festsäler for their meeting. In his history of the German revolution Müller described the informers as ‘characters who had business written all over their faces’ (ibid.).

[4] Ibid. The description of Müller is based on the photo (date unknown) on ibid., p. xv. The last-minute nature of the ‘entirely improvised planning’ for the June 1916 srike was presumably due to the fact that the trial’s date was only announced a few days in advance (Hoffrogge, op. cit., p. 37; ‘Liebknecht on Trial’, New Zealand Herald, 27 June 1916, http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NZH19160627.2.45.30).

[5] ‘[T]hough they represented many female workers and led them in strikes’, the Revolutionary Shop Stewards (see note 10. below) were all male (Hoffrogge 1, p. 29, n.28).

[6] F.L. Carsten, War Against War: British and German Radical Movements in the First World War, Batsford, 1982, p. 83.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid. Small demonstrations, numbering in the hundreds, also took place in Bremen, Essen, Hamburg and Stuttgart (ibid., pp. 83 – 84).

[9] Hoffrogge 1, p. 77.

[10] Though we will use it here throughout, the name ‘Revolutionary Shop Stewards’ was not actually chosen until November 1918 (Ralf Hoffrogge, ‘From Unionism to Workers’ Councils: The Revolutionary Shop Stewards in Germany, 1914 – 1918′ [hereafter, ‘Hoffrogge 2’], p. 87 in Immanuel Ness & Dario Azzellini (eds), Ours to Master and to Own: Workers’ Control from the Commune to the Present, Haymarket, 2011).

[11] Harry Harmer, Rosa Luxemburg, Haus, 2008, p. 97.

[12] Harmer, op. cit., p. 88; Carsten, op. cit., p. 13. In doing so, the SPD was acting in line with the official policy of the Second International, an international grouping of socialist parties from around the world, including the SPD, the British Labour Party and the French SFIO. At a special 1907 congress in Stuttgart the International had famously bound its members, to ‘do everything to prevent the outbreak of war by whatever means seem to them most effective’ (Douglas Newton, British Labour, European Socialism and the Struggle for Peace, 1889-1914, Oxford University Press, 1985, p. 168). During the run-up to the First World War, the SPD’s George Ledebour would cite the British Labour Party’s failure to follow the SPD’s example in his arguments with Keir Hardie and Édouard Vaillant: ‘By what right do you take it upon yourselves to commit other people to the general strike against war when you do not in yout country take up the same anti-militarist position as the socialist [parties] in all other countries? So long as you vote the budget, and thereby the arming of the British soldiery, you cannot come to us with more far-reaching proposals’ (ibid., p. 259).

[13] Carsten, op. cit., p. 15.

[14] Carsten, op. cit., p. 12. Though a small minority of delegates opposed approving the war credits, in the end they all followed party discipline and voted in favour ‘without a single dissenter’. Carsten offers several reasons for the SPD’s volte face: genuine ‘nationalist enthusiasm’ on the part of some; fear that the SPD would be destroyed in a nationalist backlash if it opposed the war; and the desire to ‘prove themselves good Germans’ in the hour of ‘danger of the Fatherland’ (ibid., p. 17). Fearing its seizure, the SPD sent the ‘party [treasure] chest’ to Switzerland on 31 July (ibid., p. 15).

[15] Hoffrogge 1, p. 24. This took place at a conference on 1-2 August 1914.

[16] Carsten, op. cit., p. 19; S. Zimand (ed), The Future Belongs to the People, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013 [first published 1918], p. 9. When he spoke to a meeting of left-wing SPD members in Stuttgart in September 1914, Liebknecht was strongly criticised for having followed party discipline. He told them that ‘he was deeply moved and pleased by this criticism which he considered entirely justified’ (Carsten, op. cit., p. 22).

[17] The preliminary charge accused Liebknecht of ‘having set on foot a treasonable undertaking’, namely ‘abolition of the standing army by means of the military strike, if needs be conjointly with the incitement of troops to take part in the revolution, by writing the work Militarism and Anti-Militarism, and causing it to be printed and disseminated, in which he advocated the organization of special anti-militarist propaganda, which was to extend throughout the whole Empire, and conjointly with it the setting up [of] a Central Committee for conducting and controlling same, and making use of the Social-Democratic Young People’s Organizations for the purpose of organically disintegrating and demoralizing the militarist spirit …’ (Karl Liebknecht, Militarism and Anti-Militarism, Rivers Press, 1973 [first published 1907], pp. xi – xii). The court ruled that ‘all copies of the work … as well as the plates and formes for their production, are to be destroyed’ (ibid.).

[18] Zimand, op. cit. Liebknecht received an 18-month sentence for the 1907 conviction (Harmer, op. cit., p. 82).

[19] Carsten, op. cit., p. 21.

[20] Zimand, op. cit., p. 15. The quote is from a letter to L’Humanite by Camille Husymans, secretary of the Second International’s permanent bureau.

[21] Hoffrogge 1, p. 24. His fellow delegate Fritz Kunert also resisted the vote by hiding in the Reichstag lavatory during the vote (ibid.).

[22] Liebknecht was called-up on 23 March 1915, and served as a Schipper (work-soldier) ‘assigned to tasks such as digging trenches rather than combat duties presumably because the government did not trust him with a weapon’ (Zimand, op. cit., p. 36; Hoffrogge 1, p. 36).

[23] Zimand, op. cit., pp. 36, 38; pp. 44 – 47. Liebknecht was expelled for ‘gross infractions of party discipline’ by a vote of 60 – 25.

[24] Hoffrogge 1, p. 6.

[25] Hoffrogge 2, pp. 87 – 88. According to Muller, the initial organizing started ‘right after the outbreak of the war’ and ‘[i]t took less than a year for the circle to widen and to extend to … sectors of the war industry’ beyond Berlin’s iron and meal workers (Kuhn, op. cit., p.29).

[26] Hoffrogge 1, p. 29.

[27] Hoffrogge 1, p. 29. According to Hoffrogge the core of the organisation ‘had only fifty to eighty members at any given time’ (Hoffrogge 2, p. 88). The total number of Stewards is unknown, but the entire network (presumably at its peak) was later estimated by Müller at over 1,000 (Hoffrogge 1, p. 29).

[28] Ibid., p. 9. Rosa Luxemburg, in contrast, employed servants, and ‘the upper echelons of the SPD who were her closest friends’ likewise ‘found life impossible without them’ (Harmer, op. cit., p. 59). ‘It is possible that Luxemburg’s only real contact with the working class may have been though servants and [her] audiences applauding’ (ibid.).

[29] Hoffrogge 1, pp. 11, 13.

[30] Müller’s opposition was initially aimed at the Burgfrieden rather than the war itself (ibid., p. 32)

[31] Ibid., p. 26.

[32] Hoffrogge 2, p. 87.

[33] Hoffrogge 1, p. 34. Of course, anti-war activism in wartime Germany was not confined to the activities of Liebknecht and the Stewards. For example, in March 1915 several hundred women demonstrated for peace (and against shortages) in front of the German Parliament – an action that was repeated by over a thousand demonstrators, mostly women, on 1 May, resulting in dozens of arrests (Carsten, op. cit., p. 42). To be sure, repression was more severe than in England eg. in 1916, ‘[m]ore than 50 left-wing socialists in the Rhineland received a letter from the military warning them not to speak in any public of private meeting and threatening them with arrest or imprisonment if they disregarded the prohibition’ (ibid., p. 80). Ironically, because the German government feared alienating the SPD, liberal pacifists were (at least initially) more heavily repressed than socialist opponents of the war. And this was so despite the milquetoast nature of their politics. For example, in October 1915 the Bund Neues Vaterland – which opposed annexations, but held that Russia had to be weakened in any peace settlement – was forbidden from sending its publications to its members, or even to inform them of this prohibition (ibid., pp. 50 – 51). In October 1914, Einstein – who was an early member of the Bund – had co-authored a ‘Manifesto to the Europeans’ calling on ‘intellectuals of all nations [to] marshal their influence’ to ensure that ‘the terms of peace shall not become the cause of future wars’ (David Rowe & Robert Schulman (eds), Einstein on Politics, Princeton University Press, 2007, pp. 64 – 67). Though they circulated it widely circulated amongst academics, the four authors could only find one graduate student who would sign.

[34] Zimand, op. cit., p. 81.

[35] The German original reads: ‘Wer gegen den Krieg ist, erscheint am 1 Mai Abends acht uhr Potsdamer Platz (Berlin). Brot! Freiheit! Frieden!’ We are grateful to Ralf Hoffrogge for providing us with a scanned copy of this flier. According to a later press report, Liebknecht still had 1,340 copies of the flier on him at the time of his arrest (Liebknecht’s sentence’, Auckland Star, 30 June 1916, http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=AS19160630.2.62.2&cl=&srpos=0&e=——-10–1—-0–

[36] Carsten, op. cit., p. 83; Zimand, op. cit., p. 82. This unnamed eyewitness wrongly states that the demonstration took place in the afternoon rather than the evening.

[37] Zimand, op.cit., p. 86.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Carsten, op. cit., p. 83.

[40] The Berlin strike lasted for 2 days in Berlin, the Brunswick strike 1 day (Carsten, op. cit., p.83). Liebknecht was initially sentenced to 30 months imprisonment, though this was subsequently increased to 4 years and 1 month (Zimand, op. cit., p. 92; Carsten, op. cit., p.83). In court Liebknecht declared: ‘I stand here to accuse, not – to defend myself. Not political truce, but [class] war is my slogan. Down with the war! Down with the government!’ (ibid.). When he was finally released in October 1918, some 20,000 people greeted him at the railway station where ‘he was carried shoulder-high from the platform by soldiers decorated with the Iron Cross (ibid., p. 215).

[41] It is worth noting that no explicitly political strike of any size ever took place in Britain during the war. Indeed, ‘hardly any of the British strikes took on the political and anti-war nature that some of the strikes in almost every other European nation possessed’ (Adrian Gregory, The Last Great War, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 202).

[42] Hoffrogge 1, p. 38.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid. Following the June 1916 strike the two groups did work on plans for a follow-up strike in August 1916. When the Stewards decided not to participate the Spartacists went ahead anyway, and issued a call for the strike. However, ‘without the Shop Stewards’ participation, it received little response’ (ibid., p. 38).

Liebknecht considered the Stewards to be (in Müller’s words) ‘a club of feral bourgeois philistines who met in secret and never informed the world of their existence’ (ibid., p. 62). Müller and the Stewards, on the other hand, dubbed the Spartacists’ constant demands for action – ‘hop[ing] that street fights would escalate the tension and bring about a revolutionary situation’ – ‘revolutionary gymnastics’ (Hoffrogge 2, pp. 90 – 91). Nonetheless, both groups benefited from the contact between them. Without the Stewards the Spartacists had no way of mobilising tens of thousands of workers, but the Spartacists literature also played a key role in radicalising the Stewards (ibid., p. 92).

[45] Carsten, op. cit., p. 125; Hoffrogge 1, pp. 42, 51. Once again, the Stewards were the driving force behind this strike, though this time they chose to use the general assembly of the Berlin DMV, where they were a powerful force, to call it (ibid., pp. 40 – 41).

[46] The strike, which began on 17 April 1917, was called off by the chairman of the Berlin DMV after a single day. However, some 50,000 workers continued striking until 23 April, electing a workers’ council to represent them and expanding their political demands to those listed (ibid., pp. 42 – 43). Müller’s arrest, which many workers believed was the result of the DMV’s leadership informing on him, became the strike’s first political demand. Ironically, the union’s leadership had ‘wanted to prevent the strike or at least reduce it to purely economic demands’ (ibid., pp. 41 – 42). The SPD and union leaderships acted to neutralise all three of the big political strikes in the years leading up to the revolution, with the SPD’s chairman, Friedrich Ebert, later claiming ‘that he and his party had only participated in [the January 1918 strike] to slow it down and stop it as quickly as possible’ (ibid., pp. 37, 41 – 42, 54 – 55).

[47] Carsten, op. cit., p. 132. Ths strike started on 28 January 1918 and ended on 3 February 1918 (Hoffrogge 1, pp. 49, 55).

[48] Murray Bookchin, The Third Revolution: Popular Movements in the Revolutionary Era. vol. 4, Continuum International, 2005, p. 12.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Hoffrogge 1, pp. 54-55.

[51] According to Hoffrogge ‘[l]arge numbers of revolutionary-minded workers continued their agitation at the front, whether by organising or through private conversations’ (Hoffrogge 1, p. 56). According to Müller, these activities ‘could not dent the army’s iron discipline until the summer of 1918, but as defeat loomed, they became increasingly effective’ (ibid.).

[52] Ibid., pp. 56, 64 – 65. The man Müller had nominated to replace him in the event of his arrest, Emil Barth, organised the purchase and collection of weapons, which were hidden in private homes. Money to purchase weapons was also obtained from the Soviet embassy (ibid.).

[53] David Stevenson, 1914 – 1918: The History of the First World War, Penguin, 2005, p. 496. General Ludendorff, the de facto head of Germany’s war effort, had ‘concluded that Germany must seek peace and form a parliamentary government for this purpose’ on the morning of 28 September 1918, and at his insistence the German cabinet sent a note to US President Wilson ‘requesting [him] to take in hand arrangements for an immediate armistice and for peace negotiations’ on the evening of 4/5 October (ibid., pp. 469, 471). By the beginning of November matters were moving fast. On 5 November, Ludendorff’s successor, General Groener, was briefing the government ‘that resistance to the Allies was possible for a while: munitions would last until the spring, although the divisions could get no rest, and the railway situation was ‘stretched to the extreme”. However, by the next day ‘the news from Kiel, the developing American drive towards Verdun, the threat of invasion from the Tyrol, and his information about home opinion had persuaded him that Germany must ask … for terms at once’ (David Stevenson, With Our Backs to the Wall:Victory and Defeat in 1918, Pengiun, 2012, p. 533).

[54] Carsten, op. cit., p.218; David Stevenson, 1914 – 1918: The History of the First World War, Penguin, 2005, p. 492.

[55] Carsten, op. cit.

[56] Ibid., pp. 218 – 219.

[57] Stevenson, op. cit., p. 493; Bookchin, op. cit., p. 19.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Note in Einstein’s lecture diary for 9 November 1918 (Walter Isaacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe, Pocket Books, 2007, p.240).

[60] Hoffrogge 1, pp. 5, 70 – 71.

[61] Ibid., pp. 68, 71.

[62] Bookchin, op. cit., p.2 3; Hoffrogge 1, pp. 69, 71.

[63] Harmer, op. cit., p. 124. The crux of the matter was whether Germany would become a capitalist parliamentary democracy, dominated by an ‘economically privileged minority’ and the forces of the old order, or if instead the workers’ and soldiers’ councils that had sprung up during the revolution could become the basis for a radical re-organisation of Germany’s political and economic system (Kuhn, op. cit., p. 46).

As elaborated by Müller and his fellow Steward Ernst Däumig, the latter would involve the creation of parallel structures of economic and political councils, at whose bases would be councils directly-elected in workplaces and geographical constituencies respectively (Hoffrogge 1, p. 111). Higher-order councils (eg. municipal, regional or national ones) would be elected by the members of the councils on the level immediately below, giving each structure a pyramid shape.

Central to the idea were the principles that ‘the bodies of the council system [could not] hold any powers long-term but [had to be] under constant control by the voters who [could] recall councils or council members whenever they ha[d] lost their trust’, and that employers could not join the council system (Kuhn, op. cit., p.52; Hoffrogge 1, p. 110).

Its adherents believed the council system to be the only way to realise a set of political goals that were generally agreed on by all German radicals, such as breaking the power of the military, and socializing the biggest industries (Kuhn, op. cit., p. 28). As Däumig put it: ‘[I]f the workers are not involved, if they are kept dormant and separated from economic affairs, then socialization can either never be realized or it will only turn into state capitalism, into monopolization against the will of the workers’ (ibid., p. 48).

However, despite their radical potential, ‘[o]nly a minority of [council] participants wanted to make the councils a permanent institution’, and the government was able to dismantle, repress and / or neuter the councils in short order (Carsten, op. cit., p. 231; Hoffrogge 1, p. 143).

[64] Harmer, op. cit..

[65] Bookchin, op. cit., p. 22. The Prince had asked Ebert: ‘If I succeed in convincing the Kaiser [to abdicate] , can I count on your support in fighting the Social Revolution?’. Ebert had replied: ‘Unless the Kaiser abdicates, the Social Revolution is inevitable. But I will have none of it; I hate it like sin.’

[66] Notable, in this respect, was the use of the military and government-linked paramilitary forces to crush a series of strikes in Berlin, the Ruhr region, and around Halle during March / April 1919, demanding ‘recognition of workers’ councils and the immediate socialisation of key industries’ (Hoffrogge 1, p. 117; Kuhn (ed), op. cit., p. xxvii). In Berlin, Noske, the commander of government troops, gave his men ‘carte blanche to shoot anyone identified as insurgent on the spot, even if they were willing to surrender’, and used heavy artillery in residential areas (Hoffrogge 1, p. 123). Over a thousand civilians, mostly unarmed strikers, were killed (ibid.). The ‘institutionalisation of … loyalist and reactionary units as the army of the new state’ that took place during the repression of these strikes ‘would become a decisive factor in the Weimar Republic’s destruction’ (ibid., p. 123).

[67] The ‘Spartacist Uprising’ of January 1919 – which was, once again, primarily the work of the Stewards (Bookchin, op. cit., p. 63) – is an interesting case in point. Beginning as a general strike involving hundreds of thousands of workers, it rapidly evolved into a ‘revolutionary uprising’ involving less than 1,000 armed fighters (Hoffrogge 1, pp. 100 – 106; email from Ralf Hoffrogge, 21 March 2014). Significantly, Hoffrogge notes that the uprising’s rapid defeat ‘was due not only to the army’s brutality but also to a lack of public support. Although the majority of workers supported the general strike, only a minority supported the armed uprising; after the devastation of World War 1, violence in political struggles was unpopular, even among the most radical workers’ (Hoffrogge 2, p. 97 n.15). Typically, Müller – though no pacifist – had opposed the move as being premature, ‘demand[ing] that the actions be limited to a general strike’ (Hoffrogge 1, p. 102). Over 150 people died in the fighting, and the Stewards’ reputation was so badly damaged that they ‘effectively dissolved as a group’ (Kuhn, op. cit., p. xxvii; Hoffrogge 1, p. 108).

At least one example exists of the successful use of nonviolent tactics against government forces during this period. For example, when 2,000 Horse Guards armed with machine guards surrounded and attacked the ‘red sailors’ holed up in the Royal Palace in December 1918, ‘masses of people rushed to the square’ in front of the palace, ‘form[ing] a huge crowd’ of ‘mostly unarmed civilians’ who ‘mingled with the [soldiers], imploring them to stop attacking the sailors. Unwilling to shoot unarmed civilians, they threw their rifles to the ground’ (Bookchin, op. cit., p.50). As on 9 November 1918, the key questions were the loyalty and ruthlessness of the troops. Whether such tactics could have been successfully deployed against paramilitaries selected for their hostility towards the revolution is a separate matter (op. cit., p. 56).

[68] Hoffrogge 1, pp. 91, 94.

[69] Carsten, op. cit., pp. 231 – 232.